A Poet in the Tropics of the Mind

The Making of A Young Writer

De l'Homme et de la Mer (hit this for sound)

Child, Sister, think how sweet to go out there and live together!... There, there’s only order, beauty: abundant, calm, voluptuous.

June 4, 1841. A young man paces the dock in Bordeaux alongside the steamship Paquebot des Mers du Sud. The ship’s captain, one Saliz, hurries the traveller up the gangway, squeezes his elbow and pushes him forward; Saliz was under strict orders to make sure the young man was still on board when the boat docked in Calcutta. Stops were planned along the way at Îles de Maurice and Reunion, then called l’Île de Bourbon, both of them French colonial possessions, where a few of the boat’s paying guests would debark. His presence on board was the handiwork of the twenty year old’s step-father, a well-decorated general by the name of Aupick, who had recently married the young man’s mother.

You could not choose more perfectly polar opposites than these two : one, established, a proud veteran of Waterloo vs. a twenty year old indifferent to studies, who preferred the poetry of Victor Hugo, Henri Gautier and Sainte-Beuve, which he recited out loud whether anyone asked or not. As to what else he might do in life, he was at a loss, writing to his older brother, “To choose, one must have some knowledge and I don’t have the slightest clue about the different professions.” Everything had come to a head when this proto-poet launched a few barbs at the general-usurper who had replaced him in his mother’s affections. Aupick was not amused, slapped the impertinant tyro in front of a dozen onlookers and sent him to his room. The young man, still a year short of the inheritance from the deceased father he barely knew, lived on his mother’s largesse. Once out of his room, he made tracks to the knotty streets on the hills of the Left Bank.

Young upstarts tend to get themselves in what people call trouble. Inévitable, non ? Insulting some stuffed-shirt general who’s just stolen your mother is par for the course and ought to be encouraged. Old medal-chest fought at Waterloo, did he ? It was 1841 by then and no one wanted to hear about it, especially a kid who hadn’t yet realized that childhood idylls never last. Sinister General Aupick had even more in mind : he decided to make the young man his special project, pulling his feet onto the ground of what they call the real world. A long trip to the tropics would get him out of Paris and the General’s hair for a year or more. Devil take the poets ! They didn’t fight at Agencourt or Waterloo.

The twenty year old had different ideas. He’d already written a slavish letter to Victor Hugo (no response), formed a small circle of poet friends and made early entry into the club of brilliant men with syphilis sleeping in their veins. It was the era of the Physiologies (Physiologie du bourgeois, Physiologie de l’homme marié) on sale at the kiosks, the author of la Comedie Humaine was still up and about and progress with a capital P was taking place everywhere. Our young idler crossed paths with Balzac but couldn’t get a word out, struck up protean friendships in the rooming houses of the Latin Quarter with the likes of Théodore de Banville and the flaming redhead Felix Tournachon, who made language into a game, ending every word with adar (“Ildar n’adar pasdar ledar soudar”) until everyone called him Tournadar and finally just Nadar. The tribe trouped around behind (and made fun of) Alphonse Constant, a priest whose head buzzed with so many ideas the church finally defrocked him. On his own, the young outsider frequented the café Divan le Peletier near Opéra, where he made the acquaintance of Gerard de Nerval, a writer only thirty-two years old but a world away from the budding poet in accomplishment. Nerval was approachable and the poet – no poems to his credit yet – hovered nearby as Nerval filled page after page without pause or revisions. Here was a model, this Nerval, whose poems made him famous and his best sellers comfortable, herald of a possible future for a young unknown. He looked on in awe. *

And then suddenly the young man was on the dock, facing the Atlantic for the first time, about to be torn from his mother and the world where he was making baby steps, to go where ? The tropics, that palm-studded blurry green unknown. France had profitable real estate in Asia, the Caribbean, Africa plus an undulating third of India’s east coast, and the wealth was streaming in, a reality most French chose to ignore, just as they ignore the reasons why today’s immigrants turn up in their cities.

The Paquebot, a three master, was a humble ship that apart from the goods in its hold carried a dozen voyagers outward bound, colonials, bureaucrats and businessman. The young poet lost no time scandalising them all, sleeping in a lifeboat hanging by guy ropes, shirt off (a scandal in those days; he had a delicate stomach, or so he said – people will believe anything), and more seriously, taking up with a black servant on her way home. The ship traced the outline of Africa and three months later docked at Île de Maurice, where the young tyro is greeted like royalty, the tropics provoking the first mature poem of his life. The voyage continued, making port at Reunion but when the Paquebot set sail for Calcutta, it left without him. He hung around awhile before catching the next boat back to Bordeaux and Paris, arriving months short of his twenty-first birthday and his inheritance, which he later proceeded to tear through with deliberate frenzy.

A trip made against his will, the poet hurrying back the first chance he got, and yet the only sustained voyage in the poet’s life gave him not only a lifetime supply of metaphor but something else, a subtle sense of time and the sensual life on parallel tracks, a green world far from the tumult of the modern city. Oceanic consciousness was always with him, a handy metaphor : Music often transports me like a sea! / Toward my pale star,/ Under a ceiling of fog or a vast ether,/ I get under sail.

Reread those idealized lines pinched from Invitation to Voyage at the top of this page : it’s what every voyager hopes to find somewhere else.

And what does he say about the tropics in the first real poem he wrote, one he preserved in the book that became his testament ? In the perfumed country which the sun caresses,/ I knew, under a canopy of crimson trees /And palms from which indolence rains into your eyes, /A Creole lady whose charms were unknown. Unknown to whom ? Here he pulls the curtain back, and suggests that for all her graces, she would make her greatest impression elsewhere : If you went, Madame, to the true land of glory, /On the banks of the Seine or along the green Loire, /Beauty fit to ornament those ancient manors, /You’d make, in the shelter of those shady retreats, /A thousand sonnets grow in the hearts of poets, /Whom your large eyes would make more subject than your slaves. (Translation : William Aggeler.) Again we land on that revealing last word, less generic in French : noirs. Take that, Crêole aristocracy !

The best memories of his voyage may be, for whatever weird reason, the sublime, sarcastic dreamsong written for that homey sea creature, the albatross, the bird who cannot walk but only fly, set to music by Leo Ferré. The poet sets the scene with the beauty of flight and the casual cruelties of man : a sailor poking the bird’s beak with his pipe, another imitating its limping walk...

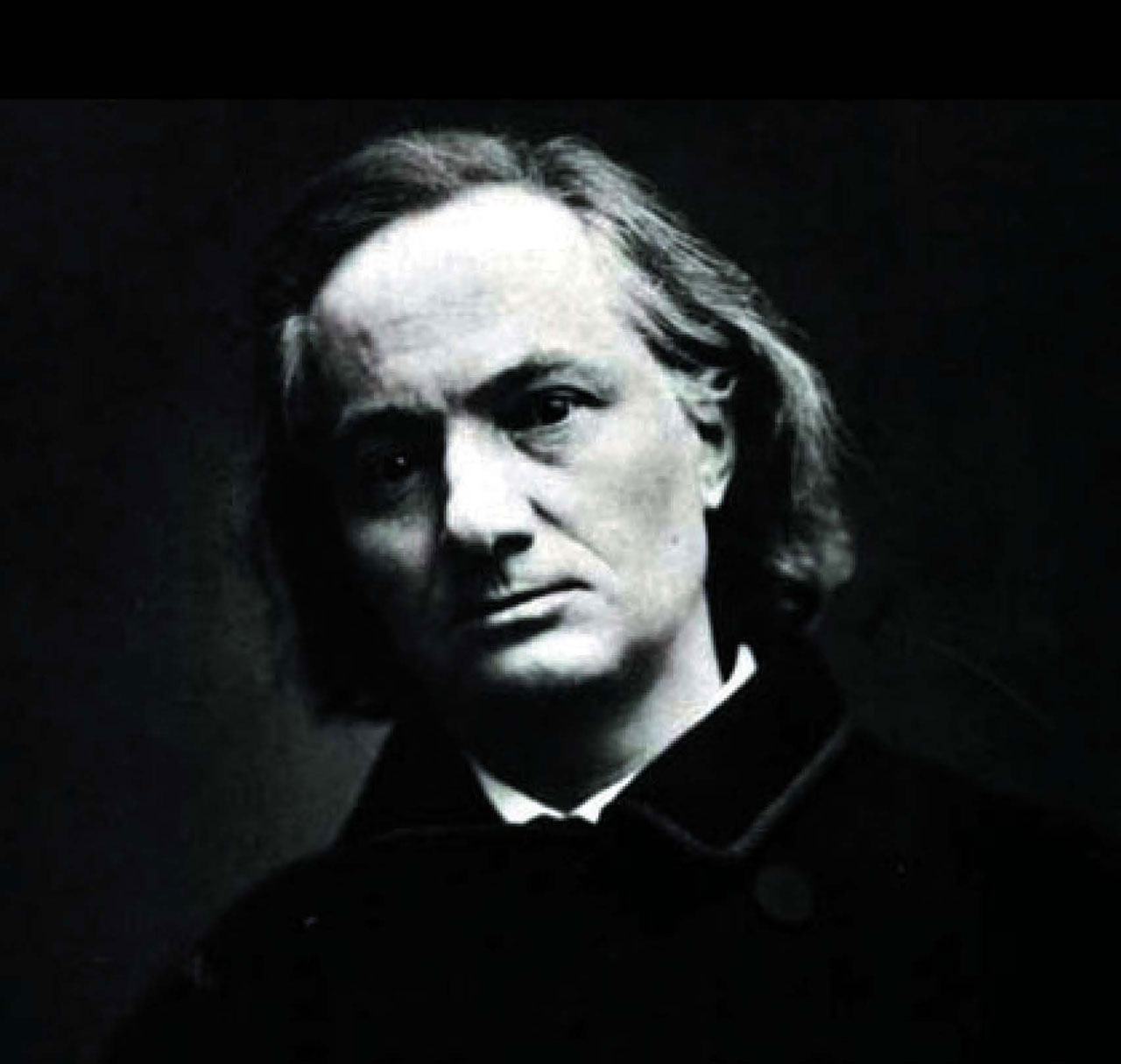

With that link the albatros is out of the bag : the poet is Baudelaire and 2021 is the bicentennial of his birth, so celebrations, lectures, readings, and exhibits are happening all over. But now we come to a wholly different question, one proposed by Patrick Chamoiseau, from Martinique, a Goncourt-winning novelist and one of the leading theoreticians of Créolité. Baudelaire looks very different from his point of view. Can we just celebrate without asking questions ? In the culte of images (“my great, my only, my primitive passion”) is Baudelaire a colonizer ? Who was this guest in their house during the age of exploitation ? (And is the age of exploitation really over yet ?) Because as much of a hurry as Baudelaire was to return to Paris, he not only took the memories of his intrigues with Creole ladies but also a deeper layer of impressions that inspired his work. Tropics of various kinds irrupt in his poems as reference and resonance. The Parisian poet of modernité and melancholie owes a debt to the far away world he barely knew. Fortunately this is France and no one is suggesting that we stop reading Baudelaire because he doesn’t conform to our stereotypes.

If the Orsay program felt very much Culture by Committee, with a sweet singing chorus and even a philosopher in tow, both Baudelaire and the tropics managed to break through at times. The mellow jazz stopped when drummer Sonny Troupé took the stage, just himself and a cajon for his version of De l’Homme et de la Mer, excerpted at the beginning of this piece. One could picture this native of Guadeloupe sitting on the shore having it out with the sea and the tragic history that comes sailing over the horizon. The lyrics here are my version; I’ve kept the lines short to echo the human cry.

Free Man Facing the Sea

Free man, you idolize the sea,

The endless mirror of your soul

As its high and mighty waves roll,

Your mind a yawning chasm, salted bitterly.

You plunge in your image to the core,

Embracing it with eyes and arms. Even your heart

Finds distraction from its urgent smart

In the sea’s wild and plaintive roar.

Both of you live in darkness and mystery :

Man, who has ever plumbed the far depths of your being?

Ocean, who knows your hidden riches, seeing

The strange secrets you guard so jealously !

Century after century you fought

Without pity, without a breath,

Eternal foes, relentless brothers,

Avid only for slaughter and death.

*************

Big Shout to Tom Player who helped with the audio, and to Sonny Troupé. I wrote about Player on Riffs and plan to interview Troupé sometime soon. His site is here. You can read a bit about Patrick Chamoiseau – Prix Goncourt for his novel Texaco – here.

*Bit of mystery why America can’t produce someone like Nerval, who could write with both hands, so to speak. I don’t mean to imitate the style but to write with one’s fingers on the pulse in the medium of choice. Do it and you’re some kind of unclassifiable iconoclast. Maybe he or she already exists ?

Continental Riffs is an entirely reader-supported publication. about life and ideas in and around France. I hit the pause button on articles - most of which are free to read - when economic necessity dictates. I hope you find the reading worth your time and thank you for subscriptions, whether free or paid - although the latter definitely helps ! Stay in touch.

Yes. I have missed your brilliant writing. Everything here is something truly special. I learned a lot and enjoy every word.