I remember the first time I chanced upon André Lebastard. I was doing a brave walk home in COVID time. Brave only because it was cold and we were supposed to be equipped with a justificatif stating the reason for our being out and about, strictly interdit after midnight. It was wintertime and I’d missed the last metro at Pasteur after dinner with friends. Long haul to Villejuif but I was full of pasta and wine and in good shape to do it.

Whether or not the police were going to bother you depended. Paris was a ghost town at that hour in that December. If there were parties going on, and there were, they were discretely out of sight. Electric taxis slid past, all of them full. I paced myself and knew I could make it, the rond point at Porte d’Italie my Most of the Way marker. Straight ahead of me, on the stretch of Tolbiac that runs along Butte aux Cailles, was a small police station, and who should be out front but four or five cops getting fresh air at what must have been one a.m. or later. No point making a sharp turn around like I’d lost my keys or forgotten the imaginary dog I was taking out for a late night promenade. I barreled by without a mask, waving my universal laissez passer, a lit cigarette. You could go anywhere with that.

(The whole thing was insane, and we know it now. Some knew it then: nobody caught the virus in the open air.)

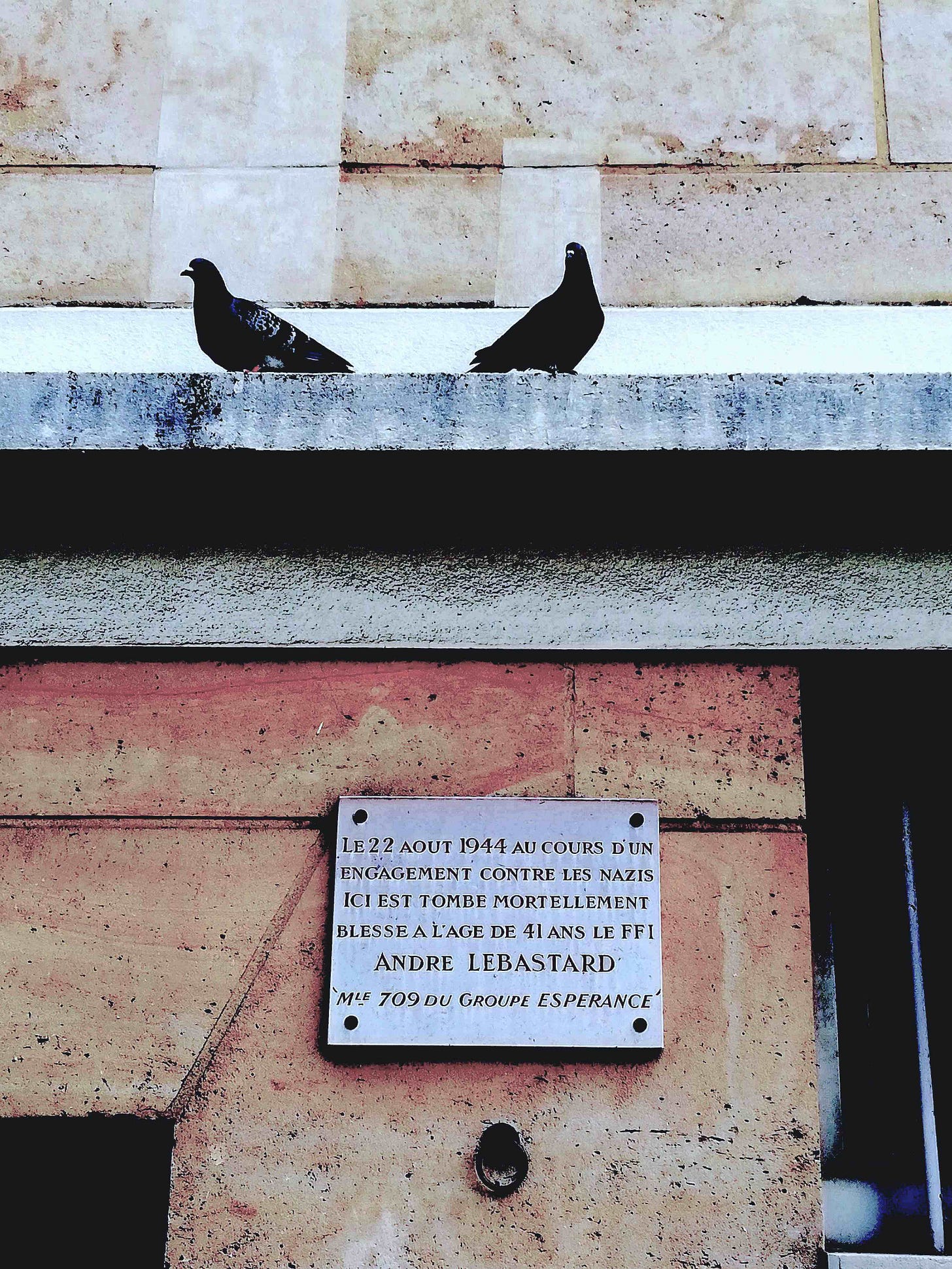

I cut through the small streets on my way to the Porte, which is how I chanced on the plaque for the fallen resistance fighter on Rue Damesme. The cold was sneaking up my coat by then but I had a good laugh over André of the unlucky name. I made a note.

André Lebastard worked for the SNCF, the national railway line. An early convert to the Resistance, he funneled information to France Libre’s secret service, BCRA (Bureau central de renseignements et d’action), about German troop movements and train diversions. He joined the Espérance branch of the FFI (French Forces In-country) early, before fighting got underway in the streets of Paris.

An early widower who remarried, Lebastard lived on rue Croulebarbe (Heavy beard) in the neighborhood that’s sometimes called that and sometimes Gobelins, after the royal manufacture on the avenue of the same name. It’s full of bank branches now and the howling sirens of police cars rushing this way and that but during confinement, a shoemaker set up shop on the sidewalk in front of the Manufacture and started repairing people’s shoes because all the shops were closed, practically daring the cops to stop him. They didn’t. People have to have shoes, and to have shoes you have to have heels and someone who knows how. He worked there for months, and I passed him on my bike on the way south from Bibliothèque Geneviève, until that closed, too.

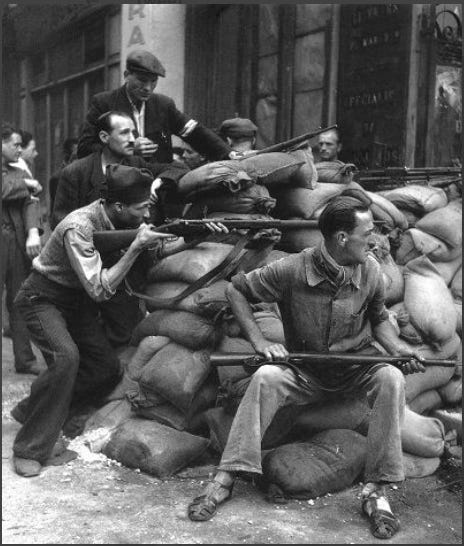

On August 22, ’44, three German tanks made a surprise attack on the barricade the Resistance had put up at Porte d’Italie. Lebastard was there with the Esperance locals, on the Boulevard Kellermann side, armed with rifles and molotov cocktails, none of which stood much of a chance against armored vehicles. Lebastard and lieutenant Georges Dudal were both seriously wounded but somehow managed to get through lines to the Salpêtrière hospital, where two days later, Lebastard died in the small hours of the night.

I’ve looked and asked around but never found a photo of the man anywhere. There must be one somewhere, maybe in the hallway of the building where he lived on Croulebarbe. I’ll have to go and look. In the meantime, one photo from the corner of Huchette and St. Jacques at the same moment in time. The men - fighting in sandals, no helmets, just rifles - are staring across the river at Notre Dame and police headquarters, from where the Gestapo ran the city.

These plaques are all over Paris, even if tourists don’t see them and people hurrying on daily rounds mainly ignore them. The area around Notre Dame and the Louvre is especially crowded because the fighting was intense in that part of the city as the Resistence took Paris back block by block. Just before Place de Concorde there is a long ribbon of names, many of them Spanish, as the battalion that moved in with Leclerc were Republicans who crossed the border after being defeated by Franco. They are part of the collective memory of Paris, the defense of the city by ordinary guys with unlucky names like André Lebastard.

I’m supposedly doing a fund-raiser around here but instead I’m busy moving house from the outskirts to inside the périphérique, the zone just south of Place d’Italie, colloquially known as Chinatown, and within that geographical area one of the towers high up in that vast 70s experiment, Olympiades. (Whose high-rises, tout petit by today’s standards, scared off the first immigrant prospects.) I’ve written about both before here and here on Riffs. I’m settling in, listening to the noise from the rooftop playground ten stories below while watching the seagulls glide around the towers. I’m getting reacquainted with the sun when the light pours in our windows high up. The cave in Villejuif was like living in a Zen monastery, with a heavy dose of Pascal. A real thinking box.

So no pitches or pleas this time. Back to the grind.