Brassaï

La Vie Parisienne

(First installment of *Parisian Lives*, a regular look at Parisians going about their lives. First is Brassaï, not with us now but who did much to shape our image of an eternal Paris. His books in discount bins outside the Strand in New York, undoubtedly played a role in luring me to this rain-soaked town. One wishes our ’30s were like his ’30s but! You don’t get to choose when you were born. At the end of this Riffs are images from Voluptés de Paris, a book that documents the Paris carnival in the Thirties.

Some new free subscribers and @ 500 readers per essay. Not too shabby but can I ask a few of you to hit the Like button ? Riffs is still a goddamn secret. Thanks!)

Biography

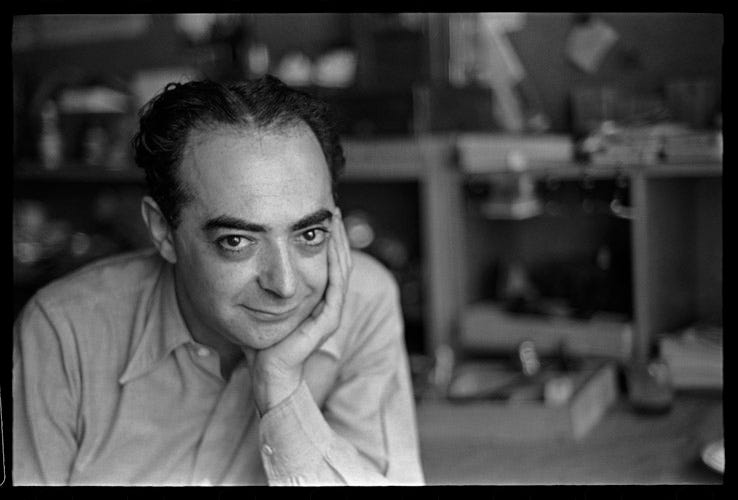

1899. Born in Brassó, a small city in Transylvania, then part of the Hungarian empire, Gyula Halas spent 1903-04 in Paris when his father taught at the Sorbonne. As a young man he studied painting and sculpture at the Budapest Beaux Arts before serving in the Austro-Hungarian cavalry during WWI. Berlin and Paris after the war, first working as a journalist before switching professions to photographer because the images ‘forced their way out,’ his way of ‘capturing the Paris night.’ The name by which Halas is known could be translated ‘Guy from Brassó,’ or just ‘From Brasso,’ now part of Romania.

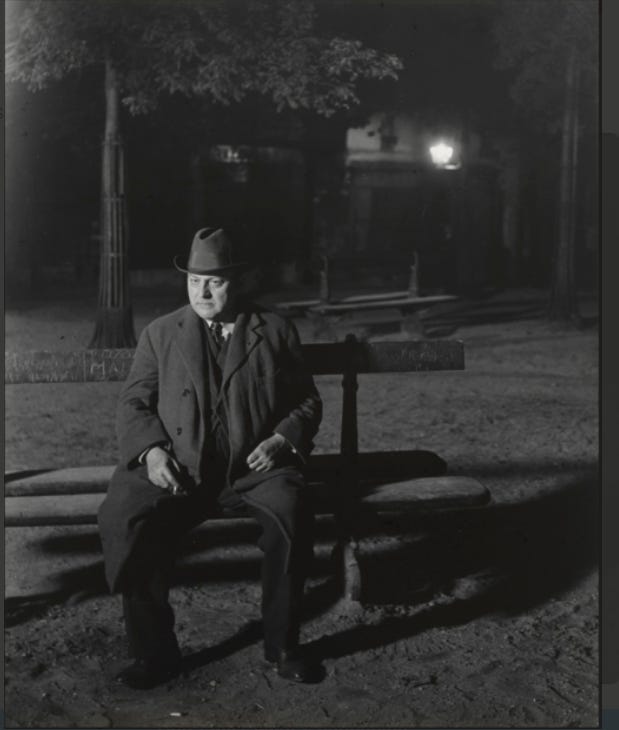

Lived in Montparnasse, then hub of the city’s artistic life in the city (and still un bon lieu de promenade far from the onslaught of the shuffling hordes), taught himself French by reading Proust solo, while befriending everyone who was anyone: Jacques Prévert, Henry Miller and the great walker of Paris, subject of one of his nighttime portraits, Léon-Paul Fargue, (I wonder if anyone reads Fargue these days) as well as, a little later, Picasso, who said, “I can judge my sculptures through your photos.”

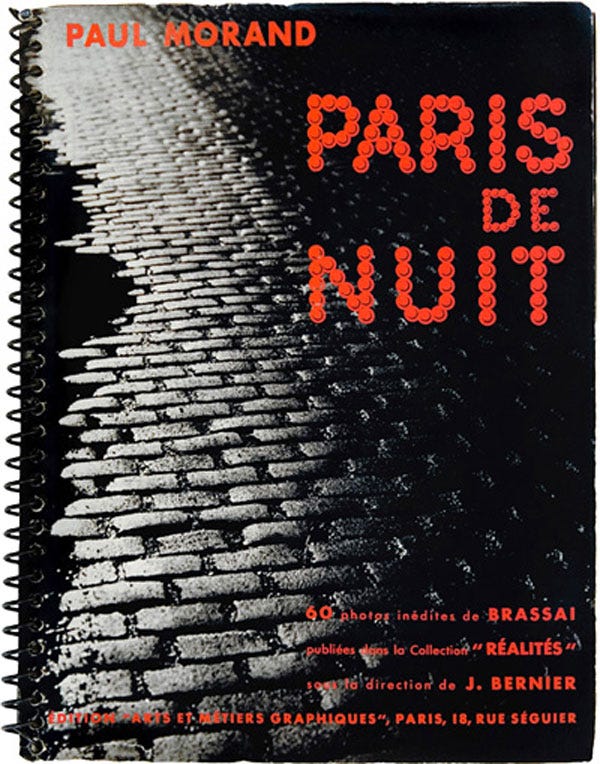

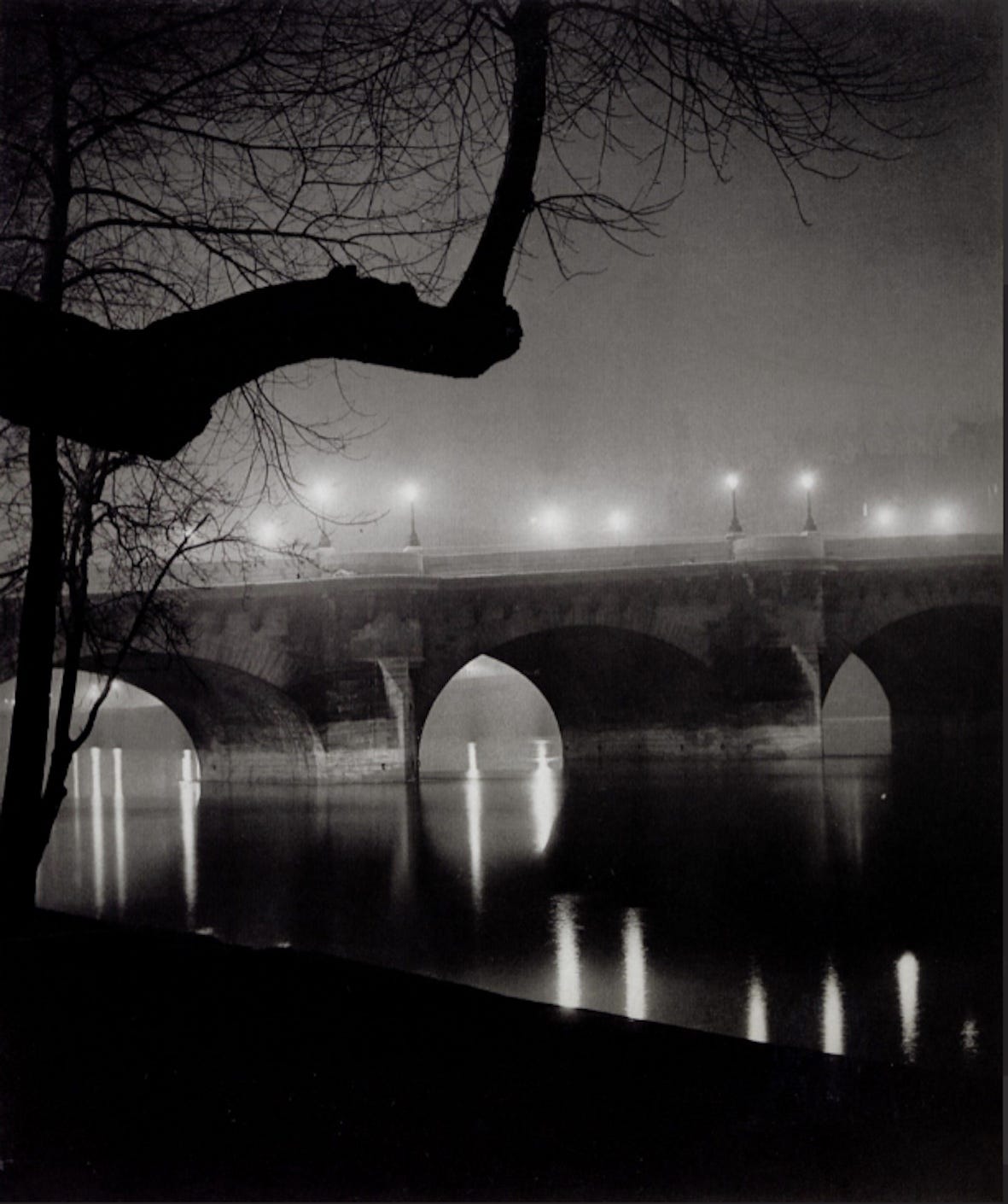

Paris de nuit was published in ’32 and made his name. Starting in 1931, he photographed the Mi-Carême, an old French tradition marking the halfway point of Lent with a masked ball. Images from that collection follow at the end of this essay.

“Night does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbs and surprises us with its strangeness. It liberates forces within us which are dominated by our reason during the daytime.”

Brassai’s describes making his way from Montparnasse to rue Grands Augustins in September, 1943: “I hesitate to go down Boulevard Raspail. One evening two weeks ago I dropped my precious pack of cigarettes. We were keeping to the dark when our faces were suddenly illuminated by search lights. ‘Hände hoch!’ We put our hands up. German soldiers wave revolvers at us and slap us around. Terrified, pedestrians hurry across the boulevard. ‘Papers!’ How can we look for our papers with our hands in the air ? The soldiers examine our identity cards, noting our names, addresses, interrogating us, going through our things...Finally they let us go but not before threatening that we’d hear from them later...For ten days, I didn’t dare go back to my apartment. I heard that a bomb had been planted at a building commandered by the Germans and skulking around in the dark, we were suspects.”

Brassai spent evenings at Picasso’s mansion photographing the Spaniard’s work, and then, passage on the street being difficult, the two men kept warm bundled up around the stove. (You might remember the image of Picasso in the wintertime by that famous stove. Wood and charcoal were hard to come by.) Brassai wrote it all down and years later, turned his notes into Conversations with Picasso, an intimate portrait of someone he knew well. There are mentions of photography in the two artists’ back and forth, with Picasso complaining that Brassaï, trained in painting and sculpture, was wasting his time with a camera. Even so, when the book came out in ‘64, Picasso said, “If you really want to know me, read this book.” That was before Françoise Gilot’s memoir came out, which, as excellent as it is, is the beginning of the Picasso the Ogre industry.

Brassaï’s Henry Miller, Grandeur Nature is a valuable introduction, as well as the book he completed just before he died, on Proust and the ‘involuntary memory’ which photography provides. Three titans of 20th century culture: Brassaï was their amanuensis.

During the war years, he returned to sculpture, variations on the human figure in stone that resemble Cycladic prehistory, while continuing with portraits of post-war figures like Henri Michaux, Giacometti, Genet and others. His visit to Dali in Port Lligat resulted in some of the best images of the much-photographed Catalan showman.

(So in a twist of fate, his friend and fellow Hungarian Kertesz the experimenter became the father of daytime ‘decisive moment’ photography, the most overplayed genre in the realm while Brassai is the unrivalled documentarian of the Paris night, which he renders in the austere silence of a platinum print. Kertesz’s work is based on glances, fleeting moments and odd perspectives while Brassai’s figures are monumental, as solid and unmoving as stone. Two sides of the coin.)

Why publish an essay about Brassaï now ? There must be more pressing issues scattered across my desk. But when the histories of photography and Paris intersect I can’t resist. Marville up next… Unlike their painter comrades, photographers are rarely the stars of the show. The Eye of Paris Miller called his friend, always on the hunt for the intriguing object, the frame, the sensibility, in his case, the hidden world of the night. Brassaï of the demi-monde made it a lifetime habit not only to see and record but to reflect on a small corner of the Europe in his time.