Stolen Moments from a Golden Age

A Photographer in Jazz's Glory Days

Revue Délibéré in Paris just published a memoir of my friendship with the photographer Bob Parent, who of all the many men who made it their métier to capture the lives of the players, remains lesser known, especially here in France. He’s in the Smithsonian collection in D.C., his images appear regularly in the press - Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry in the Guardian yesterday - but a book of his images in France would definitely change things.

A few paras from Edouard Launet’s translation of my piece follow, a first serving of French for those Riffs readers who can hack it. If that’s overwhelming, the English is further down the page, with a soundtrack in the middle to make things easier. I hope you find this survey of a life worth your time. The full article is here : https://delibere.fr/bob-parent-souvenirs-de-jazz/

Revue Délibéré, Novembre ‘22

Lorsque je l’ai rencontré pour la première fois, Bob Parent était penché sur une table à dessin, les doigts posés sur la maquette d’une page destinée au dernier numéro d’un des journaux underground new-yorkais encore florissant. Sorties papier, ciseaux, bombe de colle et aérographe étaient à l’époque les outils de rigueur. Les articles de certains magazines paraissaient à l’envers, collés du mauvais côté, mais pas quand Bob était impliqué. La plupart des journaux étaient aussi anarchiques qu’une rave punk, remplis de dénonciations de telle ou telle figure en vue tandis que les derniers groupes musicaux étaient traités avec des panégyriques à faire rougir Jésus. Parent était plus âgé, silhouette trapue qui s’appuyait de temps en temps sur les tables, parlant comme un vieil oncle sage à la voix rauque. J’étais intrigué. Difficile de deviner qui est quelqu’un au premier regard.

Bob était présent à l’Open Door de Greenwich Village un certain 14 septembre 1953, lorsque trois hommes, inconnus du grand public, ont été rejoints par une figure ombrageuse et hantée, un homme qui ne pouvait pas jouer légalement parce que sa carte de cabaret avait été révoquée. Ils sont tous des légendes aujourd’hui, mais à l’époque, c’est par un heureux hasard qu’un certain Charlie Parker est venu rejoindre au club Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus et Roy Haynes. Monk était-il prévenu, ou Parker se promenait-il simplement, déterminé à se pointer quelque part? Plus tard dans les années 50, la carte de Monk a été suspendue elle aussi, punition cruelle pour des musiciens qui n’avaient plus dès lors de gagne-pain. En tout cas, Parent se promenait par là, probablement avec son appareil photo grand format, les pieds en bois du trépied à l’épaule, artisan à louer, vagabond errant dans les rues bondées de clubs pour prendre autant d’images que la pellicule dans sa poche pouvait en contenir.

To make trekking through two versions of the same essay easier, here’s a soundtrack : Oliver Nelson with a stellar cast playing Nelson’s Stolen Moments. Hubbard and Dolphy, you can’t go wrong.

Bob Parent was hunched over a drafting table when I first met him, fingers pressing copy-cutouts on master board for the latest issue of one of the still-flourishing New York underground newspapers. Printouts, scissors, spray gun, airbrush were the tools of choice. Articles at some of the magazines frequently appeared upside down or backward, glued on the wrong side. Most of the newspapers were as anarchic as a punk rave, filled with denunciations of any mainstream figure while the latest musical groups were treated to panegyrics that would make Jesus blush. Parent was older, a chunky, middle-aged figure who occasionally leaned back on the tables, holding forth like a knowing uncle with raspy voice. I was intrigued. Hard to know who anyone is at first glance. Impossible to know who they were.

By the late Eighties, Fusion was colder than old pasta in the fridge. Jazz was out of fashion. Denizens of the Lower East Side downtown were listening to minimalist New Wave, Talking Heads, or further out, Nina Hagen, Klaus Nomi. I was back from a long soak in Latin America, full of passion for their music at the same time David Byrne was getting his Luaka Bop label off the ground. But I had a secret : I knew something about jazz, and not just by spinning a few discs in my teen years. It went back, over a decade before, when I was a brash kid who trailed my ten-years older sister around, right into the kitchen of a Jazz club in Boston, where, not having anything better to do than stand there and look stupid, I worked as a busboy, thus meeting, among many others, Elvin Jones and Charles Mingus. I listened and befriended the players, who, when they weren’t playing were busy cracking jokes about a long-haired fifteen year old who definitely didn’t know what was what.

How the conversations between Parent and myself got off the ground I can’t remember. Probably during an argument over why some sketch I wrote appeared upsidedown on the bottom of page 29… You had to fight for column inches in those days, and nobody wanted to be buried in back. Bob’s mood changed when the subject came to jazz. Maybe I’d mentioned that Don Cherry was in town and we were hanging out. He knew Don, too. Who didn’t ! Still, how so ? And then that squawky Boston accent started rolling on about some gig at the Five Spot ages ago. I knew what the Five Spot was and where it had been, but that was it. A swift education ensued. Bob brought me up to speed at the perfect moment, when I was done dancing to the latest pop sensation.

There followed visits to his loft on Pearl Street, sliver of a street downtown close on the financial district but a bohemian world apart, in the building where John Cage had at one time lived. Bob’s space was one floor below a sulky performance artist who mainly sat around looking fascinating. Good enough for me; I fell for her hard and fast. Since I was upstairs now on a semi-regular basis, why not visit Bob below for a little fresh air ? His loft was a mess, the chaos of cactus and contact sheets spreading out in disorganized splendor. If Bob knew what he had, he didn’t let on. Iconic images ? Valuable, irreplaceable captures of legendary nights long gone ? The upscale photography market was just taking off. Who was that in that picture ? Both of us had excellent recall for faces, and we dueled over who was who. I slowly realized Bob had taken some of the more famous images in jazz history, along the way pioneering available light photography on hand-made cameras, an alternative to the blinding flashes still in use after WWII. Friendly with both Mingus and Ellington, he worked for the former on the Debut and Jazz Workshop labels, whose covers are now collector’s items.

Bob had been there at The Open Door in Greenwich Village on a certain night in September ’53 when three men, unknown to the public at large, were joined by a shadowy, haunted figure, a musician who couldn’t play legally because his cabaret card had been revoked. They’re all legends now but back then it was serendipity when Charlie Parker strolled in to a Thelonious Monk gig, Charles Mingus and the still-with-us Roy Haynes a rhythm section extraordinaire. Did Mingus mention that Bird had dropped hints about stopping by ? Did Monk have warning, or was Parker just walking around, determined to play in public ? Monk got his suspension later in the 50s, cruel but too-usual punishment to mete out to musicians and their livelihood. Parent was likely roaming around with his large-format camera, wooden legs of the tripod braced on his shoulder, a freelance artisan, a chancer wandering the club-packed streets taking as many images as the film in his pocket could contain.

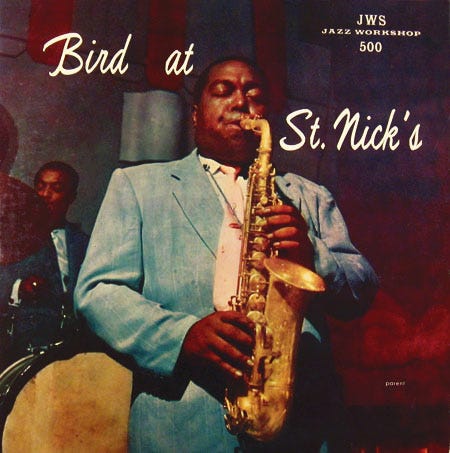

Parent’s images of Bird are something else, breaking through the aesthetic distance that was his stock in trade. The humble artisan who composed his subjects in a clean, meticulous frame was swallowed whole by a gigantic figure, a stone god in the temple of sound. Parent admired the musicians – but he wasn’t one. He was hip to the mystique but outside it, an icon-maker in the church of Jazz-Truth. His famous photo of Lester Young is instructive: Prez sits on a chair on the grass, no one around him, a forbidding, solitary figure. The image is poetic, haunting – and polite. Parent keeps his distance. Parent’s Bird at the Open Gate walks into the image the same way he walked into the club, like a colossus.

Parent had trekked down to New York from Boston in the postwar years, encouraged by his high-school friend Nat Hentoff, the jazz writer and civil libertarian. Originally French-Canadian, his family had settled in and around Boston, like so many (like Kerouac’s) after the 19th century Quebecois rebellions fell flat. By the early Sixties, his work was expanding in scope, taking in the Civil Rights movement in New York, photographing Che at the UN and taking part in the Civil Rights March on Washington in ’63. His cover for Our Bodies, Ourselves is an early feminist icon. It’s a crime, really, that there isn’t a European, much less a French, edition of his work.

I remember weeks combing through piles and dusty boxes with his nephew Dale after he died. 200,000 many times unsorted images: James Baldwin at the typewriter here, Malcolm X there, a trad band at a club in the ‘40s, and then, hoopla! Ellington relaxing at home.

My favorite was a contact sheet from the Lincoln Memorial the day of the Civil Rights March when King gave his famous speech. You can see a photographer’s light stand set up, a crowd of well-dressed political types huddled in back. Who should wander in to this improvised set but a barefoot Joan Baez in the company of her boyfriend, a young poet who would sing Pawn In Their Game at the event later. Some of the contact sheet was gone, nibbled by a cat. So far as I know, the images have never been printed. Not strictly a jazz image but a young Dylan is always worth seeing, nu ?

Thanks for getting this far on a subject not strictly in the Riff’s line. The Délibéré article has already helped the cause here in Paris, so maybe there will be good news down the road sometime soon.

Last week I posted about a little adventure I proposed to Continental Riff readers : with thirty new (paid) subscribers I’ll start publishing a novel here on site, a chapter every ten days or so. In France, that’s called a feuilleton, a serial. Balzac, the phenomenally dense writer (“Balzac invented the 19th century” - Oscar Wilde), wrote the first one, and many followed, not least Isaac Bashevis Singer, whose Shadows On the Hudson appeared serially in the New York Yiddish newspapers. I thought I’d better get in the game, and I’m aware you’ve got to bang the pots if you want people’s attention.

So, where are we then ? There are new paid subscriptions but we’re short of 30. Here’s a special offer for readers who made it this far down the page on a subject that isn’t Riff’s usual beat : subscribe for a year at 30 Euros or dollars and we’ll add a friend in the bargain, two for one. You get the reserved articles, one or two a month, plus the novel and your giftee does, too. How’s that ? Generous enough ? The offer stands for the next ten days, until the 27th, right through the Thanksgiving weekend. Hallelujah and pass the sweet potatoes.

Where is the widget to subscribe ?