There is no exquisite beauty without some strangeness in proportion. Francis Bacon

Impressionism is the stepchild of art history, too affable, a vagrant fairy calling you away from the museums and galleries to look at your surroundings as they changed before your eyes. Were those painters rebelling against the regimentation of the Industrial Revolution or were they the favored portraitists of the new bourgeois, or just reasonably talented young men who liked to chase women outdoors ? Degas is not Monet is not Manet but still, you had to have leisure time to make paintings like that ! Such a problematic character is hard to place in the grand procession of Western painting, and finally, after a few stabs at accommodating them, the Louvre exiled the movement to a mansion across the river, the former train station now known as Orsay where Renoir, Degas, Manet, Monet & Co. sit alongside their contemporaries, the academic artists of the nineteenth century, those demanding father figures the Impressionists rebelled against – and won, at least in the popular imagination. So spectacular was Monet’s success, he can claim three fiefs in Paris, the Musée d’Orsay, l’Orangerie and Musée Monet Marmottan. A pushy dissident, critical of all you hold dear like Gauguin will cost you time and shoeleather to find.

What’s more, there’s Monet’s garden in Giverny across the border in Normandy, one of the most visited sites in France. I confess to intense personal contradictions as I approach my weekly visits to the garden, a busload of tourists in tow. I adore the excess and search for the human element among the wild plantings. I like the stories, some of which I’ll tell here, and wonder what happened to the painter of modernity at St. Lazare or the investigator of bourgeois mores in The Luncheon, to name but two. Landscape painters have a special category all to themselves but let’s be honest: with exceptions (Claude, Cezanne), we don’t regard them as highly as those who paint the human scene. Later Monet goes further, jettisoning live bodies almost entirely, preferring to paint dawn along the river until he ends up, thirty years into his expanding Giverny kingdom, consumed by the play of light on the surface of water. And flowers, always flowers, those transitory beauties that will long outlive us. His later work and his garden suit the French mania for flowers, while violating their sense of harmonious arrangement, and feels, to this writer anyway, like a signpost for the Abstract Impressionists, so consumed by color and personal perception. All of it matches Monet’s expansive, genial character, fascinated by evanescent details, willing to paint the same scene over and over again.

En sortant de Santa Croce, j'avais un battement de coeur [...] la vie était épuisée chez moi, je marchais avec la crainte de tomber…

What are we to make of all that beauty ? Earlier in the century, the writer Stendhal stumbled out of a medieval church in Florence dizzy, overcome by what he called celestial sensations. He’d seen beauty at its apogee and felt elated, thrilled, something like the emotion the first man to see the Earth from outer space felt. Psychologists call it the Stendhal Syndrome, when la beauté les fait défaillir. Was that Monet’s aim, a terrestial paradise that would stun humans into realizing what was possible, that they could live like that ? Isn’t that why tourists come to Europe, for precisely that sensation ? The monuments are merely the fulcrum that lift the world.

The Givernois watched him with a wary eye and blocked his expansive plans for an oriental garden in the swamp that lay between the Seine and the tiny Epte tributary. What a mad idea ! So he’s made millions with those Americans who can’t get enough of his rosy imagination, women out for a promenade, luncheons on the grass ! Giverny in the 19th century was a hameau, the smallest of anything you could call a town, populated by a hundred farmers and cidermakers. What exotic varieties does this Parisian intend to introduce in this new project of his ? Wasn’t the expanding house with its large studio addition and immense backyard, which Monet put to no practical use, enough ? They knew an interloper when they saw one, and fought him every step of the way. The painter’s letters from Rouen make for jolly reading, as Monet employs every pejorative in the book to describe his recalcitrant neighbors. Tell the hayseeds to fuck off, is too kind a paraphrase. He got his way, diverting the Epte and filling in the marsh so he could create his idiosyncratic version of a waterlilly paradise, lacking the principal elements of Japanese art, severity and restraint, the urge to do more with less, so typical of an island culture. Not for Monet, no; more is more, and you are meant to tumble into the concrete of the underground passageway afterward with your head full of scent, ravished by the voluptuous extravaganza that lay at your feet. And then it’s on to the “French” garden behind his house, with more fleur de lis varieties than anywhere else in France, and half as many poppies as Afghanistan. A few visitors get carried away and have to be resuscitated by the garden crew.

Did someone say murder ?

For a moment, I was in luck. There was a shout, a splash and then a mad volley of screams. I hurried to the garden bridge, joining the crowd pointing at the water, not at its ‘sublime reflections of a floating world’ but at a black suitcase bobbing on the side where the gardeners park the skiffs. A camera on a stick passed under the bridge and drifted toward the waterlillies. Here was a story I could race home and type up ! Death, maybe murder, at Giverny. How did it happen ? Does it matter ? Art gives its characters an independent life in our dreams, to paraphrase Flaubert, and for once the Instagramers with their Perfect Moment jive stopped and joined the mad dreaming as we waited for a body to float to the surface. All of them had been there to witness the event, and no two people had seen the same thing. A writer couldn’t ask for more.

Alas, in hardly any time at all, a man began pacing the bridge, pointing at the suitcase as a caretaker hurried toward one of the skiffs. It was his suitcase which for some reason he’d persisted in carrying on his shoulder as he leaned too far over the railings in search of an image so perfect no one else had captured it before. Monet’s garden inspires things like that, as well as furtive gardeners who snap poppies by the neck and thrust the seedpods into their purse to take home to Connecticutt.

The man got all his possessions back. No body was ever recovered.

How He Got There

How Monet found Giverny is an interesting story. The year was 1883 and Monet was living in Poissy, one of innumerable lodgings up and down the Seine from Paris to Le Havre, where he was typically behind on the rent and at that moment, living with two families at the same time, his own and that of Camille Doncieux, who’d recently lost her husband. Devoted to his wife Claude, the affair with Doncieux would continue into the next century. The crowded house was evidence of Monet’s generosity, while he was tearing his hair out over how to end his vagabond existence. Unable to resolve the issue, balancing the needs of the two women and their children, he thought of a Sunday diversion, a train ride out into the country, just the kind of thing to liven household spirits. He roused the troops and assembled, they were heading into the depths of Normandy when the train came to a sudden, lurching stop. Riders clambered out to see what had caused this jolting surprise only to find a wedding party on the tracks, lifting bottles of pommeau in honor of the newlyweds, a dangerous celebration full of poetic resonance. Monet took the opportunity to walk around and look at the houses and marshland and solved all of his problems at once, falling under the spell of the hill country and relocating to Giverny as quickly as he could. He lived there productively until 1926, churning out the waterlilly and river scenes when not planting and grafting his two garden fantasias, his version of a Franco-Japanese floating paradise getting underway in 1893 after he’d finally wrested the swamp from the Giverny farmers. (Maybe they imagined they’d have to dress in kimonos and drink saki to suit Mr. Impressionist.)

The problem with this story is I can’t remember if it’s true or not. I read it somewhere but where ? The two families, the straightened circumstances in Poissy, the Sunday trip – yes. Where were they headed ? Not to Giverny; the train stops further down the line in Vernon. The wedding party on the train tracks ? Too perfect to be true, I tell myself. Does it matter ? I checked my sources, looking everywhere for it. It was only when I gave up, absentmindedly typing in wedding party on the train tracks that I found a site with images from half a dozen countries. It seems to be a thing to do, to celebrate a marriage and ward off evil spirits. Maybe I dreamed the whole thing up. Does it matter ?

The Bad Gallery of JG, esq.

I get to Giverny as early as I can, when my specimen subjects are just stepping out on the stage lit by the rising sun, before visitors reach full swell. There’s only one gun in the arsenal of my out-of-date, cracked-screen portable cell and that’s the panoramic lens, which, with a good angle (typically on my knees) and a steady hand, I can occasionally grab some small fraction of the thingness of flowers large or small, some hint of their presence in our fleeting space-time. I let the long exposure soak up as many visible intensities as possible. I steal the best images when I’m in bad shape, after a night of sleep in broken interludes, when I’m tempted to sit on a bench for a smoke, letting the crowds drift by in their shuffling promenade from one astonishment to the next.

Along the way I meet a fair few gardeners and horticulturists, typically keen to share their expertise. One or two would like to « take my clippers out and get to work, » as one man put it before his wife restrained him. Monet went overboard and to the current admins’ credit, the gardens are fastidiously maintained in a state of excess, of too much too much and more, a delerious haven of scent, tendrils, dirt and decay. Of course I’d go for more. There ought to be a tiger prowling the flowery lanes, or maybe a reënactment of that wedding party in the French gardens behind the house, or a Samuraï with an unsheathed sword pacing the underground passage that leads to the waterlillies. Let the gardener take out his clippers and do battle with that !

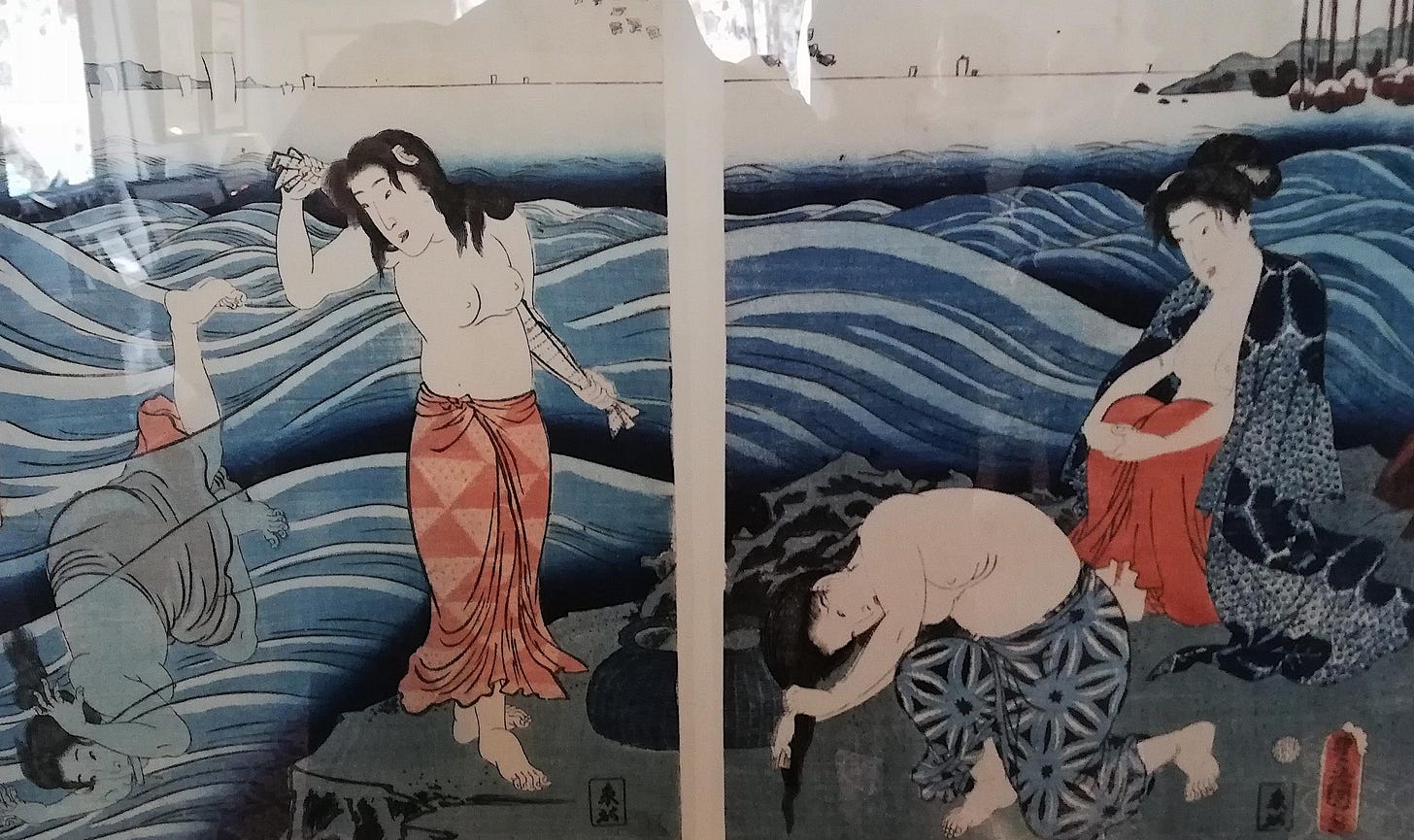

Giverny’s real feast are the Japanese prints in the old master’s house, Hokusai, Hirosige and more.

That permanent exhibition, so full of the human activity absent from the second half of Monet’s career, lets us see the Japanese in their landscape, in the bathhouse or fishing, standing by a waterfall in an unruly pictorial landscape. Monet himself is busy elsewhere, still following his obsessions, which is the one and only rule for artists. The garden is his pleasure palace, the work of a fanatic. We applaud the fanaticism while watching the tourists swoon, even if we suspect Monet was a good bourgeois at heart. That’s hardly a sin in France. But only the Japanese originals give us the thrill of discovery, the sensation of strangeness and an immense distance between the art and ourselves that Bacon described.

This essay is the 100th on Riffs. There should be more.

If freebies make my day, paying subscriptions keep this site afloat. I’ve set the pay rate as low as Substack will allow. I tend to publish in spurts, when there’s time to bring a few articles around, in between all the imperative engagements an immigrant who’s waiting on his papers has to do to keep bread on the table. Leave a trace of yourself behind in the Comments section, and if you can, make a donation large or small. Merci d’avance.